Local, Slow, and on the Street

Exploring the Roots of Urban Agriculture in MexicoÂ

by Devon G. Peña

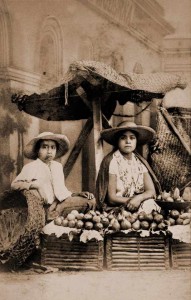

Every now and then a photograph really speaks more than a thousand words. The accompanying 1865 photograph shows two fruit and vegetable vendors in Mexico City. Judging from the architecture in the background, the photo was most likely taken inside the  historic core, perhaps close to the Zócalo.

historic core, perhaps close to the Zócalo.

A lot of commentary has been made about this photo. One thread of comments emphasizes the perceived poor condition of the ambulantes (mobile street vendors). How one can surmise this seems difficult but one comment posted recently to Facebook argues that the photograph demonstrates “The poor condition of the vendors, which can still be seen in the streets of Mexico City today.â€

However, even by today’s standards, these vendors actually look fairly well dressed and healthy. These lamentations about the urban poor strike me as betraying a modernist urban sensibility and class bias. If anything, given the source of the comments on Facebook, they illustrate a widespread failure, common to what I can only characterize as petit-bourgeois intellectuals, to understand that for many people street vending is as much a way to earn an income as it is a social and community-building activity — a way of life even.

When I see this photograph, something entirely different comes to mind. It is not poverty that I see, but abundance, culture, and right livelihood. The photograph tells me that Mexicans have done local, slow and deep food for a long time. We have practiced urban agriculture from the start and farming in the backyard and on rooftops as well as food vending in sidewalk and plaza markets have been standard activities in the city since the time of the Colhua Mexica (Aztecs).

In the Southwest, the Chicana/o Mexicana/o compact town or ‘urban village’ form of the 19th century was really a second form of urbanism preceded by the indigenous pueblo builders (see Arreola 1998, Mendez 2005).  Well into contemporary times, Chicana/o urbanism has been characterized by a preference for dense neighborhoods with proximate circulation networks that allow people to live, work, play, and socialize in the same overlapping local spaces (DÃaz 2005).

The contemporary urban vecindad form takes some of its cues from the urban cultural landscapes of pre-contact indigenous forms. Barrio urbanism, to borrow David DÃaz’s term, directly incorporates design principles rooted in the metropolitan vernaculars of the Colhua Mexica at Tenochtitlan-Tlatelolco that favor high density as well as an abundance of common and agricultural spaces.

In many parts of the Southwest, the contemporary urban village vernacular architectural and landscape forms evolved from earlier traditions embodied by hybrid forms including essentially rural patterns like the acequia riparian systems with its dense linear village clusters, acequia water webs, and resultant ‘messy’ biodiversity (abundant green spaces).

In my spatial observations in LA, I have identified six vernacular elements of alter/native design rationalities; I am calling the complex of these elements a Shifting Vernacular Mosaic. This set of shifting vernacular forms and practices is not as informal and ad-hoc as supposed by Kelbaugh and the New Urbanists. Imagine this simply as an ideal type of the Latina/o sustainable urban community.  In this perspective, the ideal community would include six interconnected components that are common elements of Mexican urban spatial practices: la vecindad (residence, home) el jardÃn (garden), la plaza, el santuario, andejido (town square, sanctuary, and village commons), la tiendita, taller, y mercado (store, workshop, market), el calmecac (school, museum, gallery, performance space), and la cuenca (watershed).

Vecindad. Vecindad has a nuanced meaning as residence or neighborhood, but can actually refers to a particular pattern in the vernacular architecture of Mexican-origin communities north and south of the present-day border. Mendez (2005) suggests that Latina/o cultural inclinations made them supportive or compatible with the “compact city†models championed by the New Urbanists, but I tend to think that the vecindad form lacks either the segregationist aims of pre-World War II American patterns or their penchant for individual privacy and convenience. New Urbanists may want to create overlapping housing, workplace, and entertainment environments for the efficiency and economy and convenience it provides individual residents. La vecindad provides a similar form not for the sake of individual convenience but because the spatial logic of the culture insists on the provision of spaces for vibrant community interaction.

JardÃn. JardÃn is a garden.  The vernacular or Everyday Urbanism of Latina/o barrios includes the flourishing of urban agricultural spaces created and used by indigenous diaspora and native communities. Urban gardens are impressive for their scope, vigor, cultural significance, and role in struggles for more sustainable and just cities. El jardÃn is a communal space shaped by autotopography (self-telling through place-shaping); it results from communal expressions of ethnobotanical and agroecological knowledge; and it is part of the political demands made by Latina/o communities for open space and other environmental amenities. El jardÃn is a source of plants for medicine and traditional recipes; it is a diverse polycultural agroecological space; and it represents a connection to home spaces back in the origin-communities and is thus often the anchor for transnational place-based identities.

Plaza, santuario, ejido. The town square is not strictly speaking a religious space in the Mexican spatial model but it is imbued with spiritual, cultural, and expressive life. It is not a sanctuary for the individual to find reprieve from the crowd as much as a space for everyday life in its broadest context.  The idea of the sanctuary as a commons is based on the principle that people want to live together and interact as much as possible “out on the street,†as Kelbaugh suggests. But this still provides the design principles for communal circulatory flows that encourage cultural, civic and economic engagement in public spaces. The idea of an urban village commons is also a component here given the rise of the just mentioned Latina/o urban agriculture movement that seeks to create food secure urban environments.Â

Tiendita, taller, y mercado. Those of us who are at least in our 40s and 50s recall the ubiquitous corner tiendita (grocery store) that provided crucial, culturally-oriented food and dry goods in our childhood neighborhoods.  While the era of Walmart Superstores is part of the neoliberal agenda, numerous inner city neighborhoods are being revitalized from the bottom-up by the return of the small family-owned neighborhood grocers, craft shops, general merchandisers, other retail businesses and crafts persons that make the barrio a complete and semi-autonomous social and economically sustainable entity.

Calmecac. The school is another institution that occupies center space in the Latina/o vernacular urban landscape. While the struggle for social justice and equality on instruction and curriculum continues in the public schools, Latina/o communities are now establishing numerous small-scale educational institutions that serve particular cultural and social needs.

These might include curanderas/os at the local botanÃcas (stores that sell botanical remedies and traditional medicines), or it might include the educational activities of soccer clubs, urban farms and gardens, Chicana/o art studios, and spaces for the study of musical and other performing arts.  Some grassroots organizations are now complementing the established Chicana/o Mexicana/o museums, art galleries, dance clubs, and similar facilities that play a critical role in our daily lived experience of our multiethnic cultural heritages.

The urban farms can also play a role as calmecacs, centers for grassroots environmental, agroecological, and ethnobotanical education as the case of South Central Farm and its successors illustrates. Â

Cuenca.  Watersheds do not disappear just because people develop a dense built-environment. Judith Baca has detailed the reclamation of the concrete-laced Los Angeles River by Latina/o artists and their communities. Murals were painted across the walls that are the river’s concrete straitjacket in a campaign not so much to beautify as to reclaim and re-emplace the relationship of the community with the river. General Vallejo who proposed following the natural limits of existing watersheds designed the first county boundaries for California. This type of bioregional sensibility is a deeply held principle within indigenous cultures.

When I view this photograph, a very different historical narrative emerges: It is one that basically reminds me that we Mexicans have been into urban agriculture from the get go.

References

Arreola, D 1998. Mexican-American housecapes. Geographical Review 73: 299-315.

DÃaz, D 2005. Barrio urbanism: Chicanos, planning, and American cities. London: Routledge.

Kelbaugh, D 2001. Three urbanisms and the public realm. Proceedings of the 3rd International Space Syntax Symposium. The Network of International Space Syntax Research, Atlanta, Georgia (May). http://botsfor.no/publikasjoner/Litteratur/New Urbanism/Three Urbanisms and the Public Realm by Douglas Kelbaugh.pdf.

Mendez, M 2005. Latino new urbanism: Building on cultural preferences. Opolis 1: 33-48.

Devon G. Peña, Ph.D., is a lifelong activist in the environmental justice and resilient agriculture movements, and is Professor of American Ethnic Studies, Anthropology, and Environmental Studies at the University of Washington in Seattle. His books include Mexican Americans and the Environment: Tierra y Vida (2005) and the edited volume Chicano Culture, Ecology, Politics: Subversive Kin (1998). Dr. Peña is the founding editor of the Environmental & Food Justice blog, and is a Contributing Author for New Clear Vision.