Writing Instruction as Social Practice

What I Did (and Learned) in Barrancabermeja, Colombia

by Diane Lefer

Friends and family expressed concern when I said I was going to Colombia. Isn’t it dangerous? So I got a kick out of the tourism video Avianca showed en route: Colombia! The risk is that you won’t want to leave!

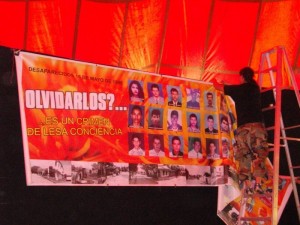

Apparently something of the sort happened to Yolanda Consejo Vargas, dancer and theatre artist born in Mexico, and her husband Italian-born director Guido Ripamonti when they found themselves in 2007 in Barrancabermeja, specifically in Comuna 7, which began as a neighborhood of squatters–people who’d been driven out of the countryside by violence, had landed in the city and were struggling to get by. The area was controlled by the guerrilla forces of the ELN. Then rightwing paramilitary death squads swept in, disrupting a Mothers Day celebration in 1998, killing and disappearing civilians, including children, while the Colombian military failed to intervene. The people of Comuna 7 organized, intent on reweaving the social fabric and creating a culture of peace. They set up what they termed an “educational citadel†to keep their kids in school and prepare them for a socially responsible future. Impressed, Yolanda and Guido wanted to be part of it. They moved in. As directors of the Centro Cultural Horizonte, they offer classes in theatre, dance and creative writing. More, they train their students who then go to the primary schools in the most marginalized neighborhood of all as volunteer arts instructors. It was because of Yolanda and Guido that I flew in May to Colombia.

Apparently something of the sort happened to Yolanda Consejo Vargas, dancer and theatre artist born in Mexico, and her husband Italian-born director Guido Ripamonti when they found themselves in 2007 in Barrancabermeja, specifically in Comuna 7, which began as a neighborhood of squatters–people who’d been driven out of the countryside by violence, had landed in the city and were struggling to get by. The area was controlled by the guerrilla forces of the ELN. Then rightwing paramilitary death squads swept in, disrupting a Mothers Day celebration in 1998, killing and disappearing civilians, including children, while the Colombian military failed to intervene. The people of Comuna 7 organized, intent on reweaving the social fabric and creating a culture of peace. They set up what they termed an “educational citadel†to keep their kids in school and prepare them for a socially responsible future. Impressed, Yolanda and Guido wanted to be part of it. They moved in. As directors of the Centro Cultural Horizonte, they offer classes in theatre, dance and creative writing. More, they train their students who then go to the primary schools in the most marginalized neighborhood of all as volunteer arts instructors. It was because of Yolanda and Guido that I flew in May to Colombia.

Barrancabermeja, home to the country’s major oil refinery, a city of more than 200,000 that until recently didn’t have a movie theatre open to the public let alone a stage for live performance, may seem an unlikely location for an international theatre festival. But that was Yolanda’s dream, and from May 21-29 hundreds of international and national theatre artists along with muralists, musicians, human rights workers and scholars converged there to offer 50 shows, 20 arts workshops, and a range of lectures and discussions all open free to the public during the First International Theatre Festival for Peace.

I knew it would be a great trip from the moment in the airport in Bogotá when I met up with Claudia Santiago and her Mexico City-based theatre company, Espejo Mutable, all of us waiting for the connecting flight. Turned out Claudia is originally from Juchitán, Oaxaca. Decades ago, I’d run away to Oaxaca and spent time in Juchitán and it turned out she knew a family I’d stayed with. We sat together on the flight and couldn’t stop talking. Claudia has been doing research and interviews among Oaxaca’s migrant farm children inside Mexico. Kids who don’t go to school, who are exposed to pesticides. She hopes to be in California soon to learn more about their counterparts working the fields here. I couldn’t wait to see her group’s production of Bidxaa, which turned out to be a visually engrossing performance for both children and adults, drawn from a Zapotec myth about transformation.

In Barrancabermeja, local dance groups welcomed us with a carnival parade. Then, in a tent set up on the lawn between the city’s one library and the satellite campus of the state university, as many as 800 spectators each night enjoyed productions ranging from breathtaking ensemble work from the youth of Comuna 7 to circus theatre from the aerialists of Venezuela’s Circomediado.

Teatro Dell’Elce, from Italy, solved the language problem with a play without words while from Israel, Yoguev Itzhak projected subtitles for the story of a Palestinian Arab boy in a Jewish hospital. Mexican companies Teatro Tequio and Norte Sur Teatro from Tamaulipas presented uncompromising depictions of the violence now troubling their homeland. Solo performers included my two wonderful roommates, Andrea Lagos from Chile and Silvana Gariboldi from Argentina. And of course, my frequent collaborator, Hector Aristizábal–Colombian now living the US–who would perform Viento Nocturno, the Spanish-language version of our play, Nightwind, about his arrest and torture by the US-trained Colombian military, his brother’s murder, and how he transformed his desire for violent revenge into work for peace.

Monday through Friday from 9:00 AM to noon, Claudia and Espejo Mutable were Hector bussed to a nearby village to work with little children who usually have no access to arts education. Andrea and Silvana were teaching street theatre and physical theatre techniques. Hector was facilitating workshops using the techniques of Theatre of the Oppressed, and I was given space in the national vocational and technical training center where I led a series of writing workshops in Spanish–an assignment I’d accepted, though the idea seemed just as improbable as the theatre festival itself. Even more improbably, just like every aspect of this improbably wonderful trip, it worked, and so I’d like to share some of what I did in Barrancabermeja–workshops that were, as you might imagine, rather different from those I used to co-facilitate in the MFA program at VCFA. Different because my plan was to offer writing workshops for people who think they can’t write–often because that’s what they’ve been told.

I’ve been experimenting with ways to demystify the act of writing, of getting words from the brain through the hand to the page with people who’ve felt silenced by trauma or by marginalization, like some of the kids I’ve worked with in Los Angeles who’ve been labeled illiterate or stupid, whose experience of formal education is one of frustration, disrespect, and failure. In Barrancabermeja, my group of guinea pigs was a wonderful mix of young children, high school and college students, teachers looking for ideas to take to their classrooms, and adults from the city, curious enough to take time off from work and try something new.

The first day everyone got two narrow slips of colored paper. I invited them to write a realistic compliment on one piece of paper, something like I love your smile. On the other slip, they wrote a fantastical compliment, something impossible that came from the imagination. They were free to ask any question or for help with spelling. We rolled the papers up small and tight and inserted them into balloons. (When I do this with gang members or emotionally disturbed kids, I don’t hand out the balloons till I’ve checked what they’ve written to be sure there are no insults or threats.) Once all the balloons were stuffed and inflated, we hit them around the room till everyone ended up with one. Now came the part that had me worried. The plan was to ask people to sit on their balloons and bounce up and down to burst them and then read the compliments they’d received. But I wasn’t sure how people who were living through a civil war would react to the bang bang bang and beyond that I was nervous about the police and soldiers stationed in the building. Maybe balloons popping sound nothing like gunfire to people who are used to that sound in real life. In any event, the exercise went off without a hitch.

And yes, some days, security forces stood right in the room with us. Barrancabermeja is not at war these days but I’d say the city is in a state of security rather than peace. Tourists to Colombia’s cities really need only take whatever precautions against street crime you’d ordinarily take in an urban environment. But for many Colombians, the armed conflict still rages. Hundreds of participants in the festival came from rural areas where they are caught in the crossfire. The new president, Juan Manuel Santos, unlike his predecessor–rightwing Alvaro Uribe, who now teaches at Georgetown–doesn’t call people “terrorists†when they talk about peace and human rights, but death squads–some linked to politicians and to the army–still do their dirty work. After I returned to Los Angeles, Hector remained in Colombia working with a group of women trying to enforce their rights under the new “victims’ law†intended to help violently displaced people return to their stolen land. While they were meeting, a death threat was delivered. Not some illiterate scrawl, either, but a typed warning with an official looking seal, stating that these community leaders would be “exterminated without pity.†This was not an idle threat: at about the same time, a woman named Ana Fabricia Córdoba who was demanding enforcement of the law was gunned down in MedellÃn.

The reality in Colombia is that activists are still being targeted for assassination. If you gather to talk about peace and human rights, in the eyes of the death squads you are being subversive. But in Barrancabermeja, Yolanda and Guido had won for the festival the endorsement and support of the mayor’s office, the oil company, the Church, the television station, local and regional organizations, including those linked to European governments. With all this backing and good will we could speak openly and assume the security forces were there as protection rather than threat.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

I love to use Sandra Cisneros’s story “Eleven,†from the collection Woman Hollering Creek, and I took the Spanish translation “Once,†(from El Arroyo de la Llorona) to Colombia with me. The story is told in first person by Raquel, whose eleventh birthday is ruined when her teacher finds a ratty old sweater in the cloakroom, insists it’s hers and makes her wear it. Raquel tries to say the sweater isn’t hers, but she can’t make the words come out, and even when she does speak, she is ignored.

I read the story aloud, book in hand, because for people who may not have books at home or who know books as tasks they have to do for school, I want to instill the love of the printed word. After reading, I ask, “Has this ever happened to you?†I ask everyone to write a paragraph explaining the untrue thing that was believed of them. On the back of the page, they write the words they wanted to say, the facts they wanted understood.

There’s always someone who insists they’ve never been misunderstood. So I ask them to write about it happening to someone else, and how they wanted to defend that person but couldn’t find the words. Or to invent a situation. (Once in California, a little girl told me she never allowed anyone to say wrong things about her, but she admitted her brother had been unable to convince their mother of the truth when she lied about him.)

In our group, it was interesting to see how the experiences varied by age: the little boy blamed for a noisy classroom; the teenager whose mother was told she was hanging around with bad company, the college student accused of stealing someone’s notebook, and the accountant who wasn’t paid the sum agreed on by people who denied making the oral contract.

Participants created skits about their bad experiences, encouraged to portray the people who’d hurt them in ridiculous, exaggerated fashion. Then they read aloud the words they’d wanted to say in their own defense and we all shouted We believe you! We support you!

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

A women’s committee prepared hundreds of meals every day. The panel truck would pull up with stacks of plastic containers full of individual portions, everything tasty and fresh. The first day, volunteers set out tables and chairs under the trees, but it was time-consuming and burdensome. Soon we learned to take our food and sit anywhere–on the grass, against the wall of the university building seeking shade. (On a previous visit to Colombia I’d missed having hot sauce for my meals so this time I brought my own bottle, happy to share it with the Mexicans.)

Afternoons, before the performances began, there were lectures and discussion groups. I was more interested in the sessions on current politics than the academic offerings. What was the point? I thought, until I saw how participants with limited education felt honored to be included in conversations about Lacan and the unconscious, about brain evolution, and literary theory, to be able to ask “What does the word ‘intertextuality’ mean?†and be answered in a respectful way with no one talking down to them.

It made me wonder about our American penchant for dumbing down education. And, in making my workshops fun, was I condescending? I was reassured when two of the teachers asked for a copy of “Once.â€

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

Part of demystifying the act of writing is getting away from the idea that it has to mean sitting still, staring at a blank page. It can become every bit as natural as moving around, talking, doodling.

I asked everyone to invent a new product that could magically solve a social problem, draw the advertisement for it, and write the advertising copy. An adult woman invented a chocolate bar that makes you lose weight. An activist drew an injection that keeps memory alive and puts an end to societal indifference. Twelve-year-old Julieth drew a pair of cheap but magnificent “anti-prostitution†shoes. Girls who wear them become incapable of selling their bodies, something I later learned one after another of her classmates has begun to do.

Some years back, VCFA graduate and professional storyteller Judy Witters sent chills up and down my spine with her rendition of the tale that served as the basis for Chaucer’s Wife of Bath. A knight is condemned to death for raping a girl but his life will be spared if he finds the answer to the question What do women want? He is about to forfeit his head when a hideous crone gives him the answer: “sovereignty.†But he must marry her in return. On their wedding night, she tells him she is under a spell and he can break it. He can choose whether she is to be transformed into a beautiful young woman who will make his life miserable or she can remain old and hideous but will never betray him. When he allows her to make the choice–recognizes her sovereignty, she becomes both beautiful and good.

In my version, whether in English or Spanish, I try to keep the mood lighter. With children, I talk about attack or assault rather than rape. The knight gets silly answers on his quest: the palace cat thinks women want a plate of tuna; the dog thinks women want a good master. Ultimately — I admit it’s less poetic than “sovereignty†— the knight learns that “Women want the right and the power to make their own decisions about their own lives.â€

After I finish telling the story, I point out that What do women want? is a big question. What does Diane want for lunch? is a small question. I divide our participants into groups and ask each group to agree on a big question for which they want to seek the answer. Then out come the long rolls of paper so they can create murals showing the quest, asking “experts†for answers, and finally writing out the best answer the group can devise. One group asked how to be a good parent. The tiger said, “Teach your children to hunt.†The tortoise said, “Bury them in the sand and let them fend for themselves.†The human grandfather’s advice filled the entire righthand panel. One group asked how to make children value books. The television, the radio, the computer all said, “I’ve got everything you need right here.†Disgraceful of me, really, but I don’t remember what the solution was.

Local hotels donated rooms for the international artists, but apparently just one room per hotel, and so, early every morning, the Festival sent a bus which made the rounds to gather us all and to return us to our rooms at night. It was a chance to see more of the city, but after Andrea discovered our hotel was actually within walking distance, we sometimes headed out on foot. The community groups, the teachers and kids from different regions around the country, camped out on the floor of the cultural center in Comuna 7. One night we were all there for a startling performance by the Mexican group Norte Sur. It ended at 3:00 AM. Time to get to sleep. No … the kids were soon outside the building with their musical instruments. The dance party began.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

In Los Angeles, in getting a kid to write I sometimes have to convince him first that stuff in his head matters. I’ll spend an hour interviewing a young man. Then I write up the story of his life, print it out on nice paper and give it to him. Then I ask him questions about himself and this time he has to write the answers. Very often, the kid’s mind works faster than his hand and he can’t remember his answer long enough to get it on the page. I make him repeat his answer aloud until he has it memorized and then writes it down word by word. Pretty quickly these kids develop the facility of transferring thought directly to paper.

The young people in Colombia were either a highly motivated group or else their confidence has not been crushed. Even the kids who struggled a bit with spelling and grammar wrote their exercises with enthusiasm and without hesitation. Because I didn’t need to interview anyone, I asked them to interview and write biographies of each other.

The next day we held a press conference. I told them they were all journalists and could interview a Martian just arrived on earth as well as two more people of their choice, living or dead. The group chose Jesus and William Shakespeare. Three of them sat up front to play the subjects.

“But I don’t know anything about Shakespeare,†objected Izeth. Then she got the idea, “I get to make it up?†And she did. We learned Shakespeare’s first play, Hermosura, was so bad, he threw it out. That there’s controversy about who wrote his plays because while he was living in a farmhouse in Scotland, a false friend stole his manuscripts and tried to pass them off as his own. Jesus hadn’t returned sooner because he couldn’t afford the airfare. Now he’d been able to hitch a ride with the Martian. And the Martian who, we learned had four wives and many children, spoke a language that consisted mostly of cak cak cak and relied on sign language to communicate along with the help of Jesus as interpreter.

The questions kept coming, the subjects kept improvising. We learned Jesus disapproves of gossip and doesn’t like fast food. The journalists took notes. When they wrote up their reports later — some for television broadcast, some intended for the radio, some for print — I was impressed at how accurate the accounts were not to mention well written and very funny. I’d thought that coming up with questions and taking notes and — for the three subjects, doing all that while also improvising — might be asking too much. But now I think that being active, instead of passively listening to a presentation, kept them engaged and better able to concentrate later and quietly shape the material in their reports. The only errors I caught? Two people rendered Shakespeare’s discarded play as Hermoso (beautiful) rather than Hermosura (beauty). If NY Times were only as accurate as that, we’d all be better informed.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

The young people from Centro Cultural Horizonte were on hand every day as volunteers handing organizational and logistical support. They were great but I had no idea what we were in store for when they performed “Preludio,†an intensely physical, precisely choreographed story of their lives, juggling their bodies in and out of picture frames, heads thrust through rungs of a chair. Any misstep could have caused injury. We watched fights with machetes, we watched the struggle for dignity and identity, we saw violence, and death and the reconciliation of victims and perpetrators. I was left breathless, but some of the people in the audience truly couldn’t breathe. Because the performance was more abstract than realistic, I was not at first aware of the impact it had on people still traumatized by the violence in their own communities. “We were frozen,†a woman told me. “I didn’t know how we could stay here. How we could go on.†Then Hector performed and, as is his custom, followed the disturbing performance with exercises for the audience: chaotic breathing, the releasing of sounds including shouts and screams. People reacted by making images with their bodies, by expressing what they wanted to see in the world instead of what they’d already seen. We moved. We shook ourselves. We shouted. “That saved us,†the woman told me.

Movement. That’s what I want. I reject it so completely–that whole educational model of people sitting motionless, silent, in chairs.

We did theatre exercises, moving around the room, making noise as we explored what makes us feel big, and small, generous, greedy. We entered the minds and bodies of people we don’t like and then wrote monologues in their voices.

We wrote dialogues. The group divided into pairs and I gave them a first line: “Where were you last night?†or “You’re not going to like what I have to say.†They passed the paper back and forth, creating the conversation one line at a time. Then it occurred to me, what if a third person entered the scene? I interrupted some of the couples and sent them over to intervene in other conversations. But no one wanted to abandon their own entirely, so pretty soon, it was the controlled chaos of musical chairs as people ran from seat to seat, adding lines in one scene, then returning to another.

In LA, I’ve sometimes been accused (accurately) of allowing too much chaos in the room. As one employer pointed out, “These kids live in chaos. This is one place where they should have the security of order.†Which was true. It’s not that I didn’t agree, but part of me wanted them to see they could concentrate, complete a project, and achieve in spite of chaos around them. Still, my Colombian participants seemed to have had a respect for orderliness instilled in them. What was controlled chaos in Barrancabermeja would likely have been total chaos at home.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

Sunday morning I’m free and so I take a boat up to the next town, Puerto Wilches. The Magdalena River is a major transportation route in the region. Flooding this winter left many people homeless. With road washed out and bridges down, some communities remain cut off.

Colombians express shock at pictures of the tornado devastation in the US. “We thought American houses were built strong.â€

And a teenager who recently survived a car bomb and being caught in the crossfire between soldiers and FARC guerrillas said “People may change, but Nature won’t.â€

It’s hard to say goodbye. Yolanda and Guido are already planning for next year.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

Back home, after two weeks in the sweltering tropics, I walk outdoors and it feels like the world itself is air conditioned. For two weeks, I picked my way through rubble and mud and now I look at our clean streets and paved roads and think how privileged we are and wonder how long we will stay that way as we seem intent on restructuring the economy to resemble, well, Colombia’s. I think how much we take for granted and how we may lose it all thanks to a philosophy that sees the only legitimate function for government is homeland security and waging war.

I think how hot and humid it was in Barrancabermeja and yet in the tent I never smelled sweaty bodies. There was a fragrance in the air, like church incense, and though I kept asking, no one could tell me the source.

And I keep thinking about the tale I told and how dissatisfied I am in the end because of what’s missing from it. The knight learns his lesson. He reforms and lives happily ever after. But Chaucer doesn’t tell us what happened to the victim. Her story is dropped. There’s the other big question. What does the survivor of violence want? (Justice? Revenge? A gun?) What does the survivor need? From now on, I’ll need to ask that question.

During the festival, sociologist and Catholic priest Father Leonel Narváez said we need to forgive. But he defined forgiveness in an unaccustomed way. It doesn’t mean reconciliation. It doesn’t mean taking the offender by the hand. Justice must still be done and perpetrators brought to account by the State (which becomes complicated when the State has been one of the perpetrators). Forgiveness is a transaction you do not with the perpetrator but with yourself, he said. It’s how you relieve yourself of bitter hatred and resentment and desire for revenge. Father Leonel talked about forgiveness as a political virtue and a necessary daily practice in order to put an end to Colombia’s six-decades long cycle of violence.

And I thought of Rita Chairez who coordinates the Victims of Violent Crime Ministry of the Los Angeles Archdiocese Office of Restorative Justice. She facilitates support groups and accompanies the bereaved who are, in her words, “walking the path I’ve been walking for ten years now,†ever since the murders of her brothers.  “We don’t encourage forgiveness,†Chairez has told me. “We encourage healing.â€

But maybe in different words they are talking about the same thing.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

What does it mean to hold a theatre festival “for peace� Or to imagine that a writing workshop plays a role in the struggle for social justice?

As a writer, I know that words matter. Hector believes in the wisdom of the body, in spontaneity, but for me that’s only part of what we need. Visceral reactions can be manipulated so easily. Words can also incite, can trigger the mob. But for me, words–especially the written word–provide a gap, that space in which critical analysis can occur. Once the words are on the page, they are apart from me, mine and not-mine. I can look at them, read them. They let me think about my thoughts. Maybe that’s why I so much want to see people develop their writing abilities even if they aren’t “writers†and don’t want to be.

I think about violence in Colombia and in the streets of LA and in our extraordinarily punitive criminal justice system and how we believe in the efficacy of violence, that we can solve problems through the use of force and how the US has been the most powerful military force in the world for a decade longer than Colombia has been wracked by civil war. I think how even when my behavior was nonviolent, for the longest time my language was very angry and violent. When I began to control my words, I remained committed to social justice, but the rage dissipated. I began to think the rage was fueled by feelings of powerlessness, and when I controlled my own words, I didn’t feel quite as powerless.

In the workshop in Colombia, the participants spoke their own words and were heard. I have to believe that matters.

Bioethicist Sergio Osorio reminded us one afternoon in Colombia that the language we use will determine what sort of knowledge we gain. We can use language in an empirical, logical, technical way, or in a fashion that’s symbolic, poetic, and creative. We need both.

I keep thinking about the word “forgiveness.†Once we use it evocatively in a new way, isn’t it possible that something new happens inside us?

Diane Lefer is an author, playwright, and activist whose recent book, California Transit, was awarded the Mary McCarthy Prize in Short Fiction. Her stories, novels, and nonfiction often address social issues and draw on such experiences as going to jail for civil disobedience and her volunteer work as a legal assistant/interpreter for immigrants in detention. Her new book, The Blessing Next to the Wound, co-authored with Hector Aristizábal, is a true story of surviving torture and civil war and seeking change through activism and art. This article originally appeared on Numéro Cinq. More about Lefer’s work can be found at: http://dianelefer.weebly.com/.