La Lucha por la Sierra

On the ‘Continuous, Open, and Notorious Use’ of the Commons

by Devon G. Peña

Between 2002 and 2003, in a remarkable and much discussed series of three decisions, the Colorado Supreme Court restored the  historic use rights of the plaintiffs in the Lobato v. Taylor land rights case. The legendary case involves plaintiffs’ use rights on 80,000 acres of common lands in the Sangre de Cristo Land Grant (merced). This is an alterNative paradigm unfolding right before our eyes…

historic use rights of the plaintiffs in the Lobato v. Taylor land rights case. The legendary case involves plaintiffs’ use rights on 80,000 acres of common lands in the Sangre de Cristo Land Grant (merced). This is an alterNative paradigm unfolding right before our eyes…

The grant encompasses a total of 1 million acres and most of the 1843 merced was enclosed by private owners including the portion at stake in the Rael-Lobato trilogy; on the New Mexico side of the grant, some of the land ended up in the public domain as part of the Kit Carson National Forest (including portions of the Valle Vidal) but local heirs successfully re-acquired title to more than 30,000 acres as part of what is today known as the Rio Costilla Cooperative Livestock Association (RCCLA) lands.

The land in this case involves 80,000 acres of La Sierra that were enclosed in 1960 by Jack Taylor, a direct descendant of President Zachary Taylor. As the Colorado Supreme Court and lower courts deliberated the case in the mid to late 1990s and early 2000s, ownership of the land underwent quite a series of turnovers: In 1997, the Taylor family rejected an offer from the State of Colorado and local community (through La Sierra Foundation) to purchase the land. Instead, Zachary Taylor, Jr. sold La Sierra to Lou Pai, the infamous CEO of Enron Energy Services. After the collapse of Enron, in 2002, Pai sold the land to the current title holders, Bobby and Dottie Hill and their partners.

The Lobato trilogy of decisions effectively re-authorized 150 years of the exercise of rights of usufruct by heirs and successors of the original Mexican land grant settlers. The highest state Court thereby legtimized the deep relationship between local people and their watershed commons. Families that could verify they were still living and working on properties that were privy to the original 1860s hijuelas issued by don Carlos Beaubien, and who had been denied due process in the wake of Jack Taylor’s 1960s Torrens quiet title action, were to be designated as beneficiaries of these rights to the commons that the local people call La Sierra (the Mountain).

These bold and unprecedented decisions reversed four decades of often demeaning and ethnocentric misjudgments by earlier district and appeals court judges that continued to ignore the unresolved due process and equal protection problems of the case. The Lobato trilogy thus marks one of the most significant recent developments in the Chicana/o land grant restoration movement because it reversed decades of ill-advised lower court decisions that unjustly terminated the unique place-based ecological governance of common lands across the Southwest.

The three decisions, it should be noted, were not based on the logic of any claims ultimately grounded in an appeal to the confirmation of the terms of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Instead, plaintiff’s legal counsel in Lobato v. Taylor creatively and effectively pursued restoration of historic use rights by using the Master’s Tools [sic] and basing the claims on adverse possession, estoppel, and prescriptive easement – a legal strategy we will have to discuss in a later post.

The hijuelas are the coveted deeds recorded in county court clerk documents that conferred title to private long-lots in the acequia-irrigated agricultural bottom lands and also granted use rights to such inhabitants of the long-lots to the timber, grazing, and wildlife resources of the 80,000 acre La Sierra commons.

In an often overlooked passage in the third and final decision, the Colorado Supreme Court majority opinion noted the importance of this decision in terms that actually emphasize the value of the persistence of the acequia farming way of life:

“The Costilla County landowners, whose property rights are at issue, are the present-day descendants of 1850s frontier farming families who were recruited by Carlos Beaubien to move north from the Taos area in New Mexico and settle in what is now southern Colorado.

“Beaubien acted from self interest: without settlers, he could not perfect his rights to the one million-acre Sangre de Cristo land grant because the Mexican government made settlement an express condition of the grant to Beaubien. To convince these families to move north, Beaubien granted the settlers access to the wooded, mountainous area to graze their animals, gather firewood, and harvest timber to build their homes and outbuildings. Without these property rights, subsistence farming on the valley floor would have been impossible.

“At trial, many current residents of Costilla County testified that, for over one hundred years, the use of these rights was widespread by the families residing in the region. These residents testified that it was general knowledge in their communities that the Taylor Ranch could be used to graze their animals, gather firewood, and collect timber. According to trial testimony, the mountainous tract purchased by Taylor had been known simply as ‘la merced,’ roughly translated from Spanish to mean the gift or grant.†— [Lobato v. Taylor, Case No. 00SC527; emphasis added]

Of course, the reference to “subsistence farming” is an allusion to the acequia agricultural communities that settled the land grant.

The old enclosure of La Sierra by Jack Taylor, et al. has been reversed and the commons restored in a manner that remains unparalleled across the Southwest or other parts of the world where such community-based land use systems have evolved and remain under attack.

Despite the victory in Lobato v. Taylor, the process involving the actual exercise of these rights of usufruct to La Sierra by local people remains contested and, sadly, is now also a matter of litigation. There is a wave of “new enclosures” that we are only now starting to confront. These struggles are related to the late arrival of high-end subdivisions in the privatized foothills below La Sierra.

Access to the Commons and the New Subdivision Enclosures

The principal problem in the current struggle is the construction of barriers by the owners of the Torcido Creek Ranch, Mountain Lake, and other subdivisions. These barriers have been erected on roads that have been used over six generations to gain access to La Sierra for the exercise of what are now considered Constitutionally-protected rights of usufruct.

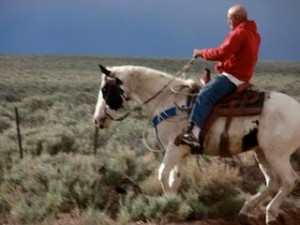

Over the decades since roughly 1984, I have participated in numerous trips into La Sierra that involved riding horseback along various paths using the Torcido Creek trails. I have always understood that, before 2006, each ride I went on with my neighbors and friends was simply part of a deeply rooted and apparently renegade [sic] custom, a longstanding local tradition of trespass [sic] or more accurately, as the Colorado Supreme Court justices described it: “the continuous, open, and notorious use” of the commons by the local people.

So, per the rationale of the Supreme Court, and local custom, this was not trespass but the continuation of a pattern of historic uses dating back to the 1840s and 50s. The people had not crossed the fence. Instead, the fence had crossed the people, as an elder retired sheepherder once told me.

This access road and related trails have been used since the 1840s, well before permanent settlement — originally by sheepherders and then cattlemen. All along, elk hunters, seeking food for the family table, have engaged in subsistence hunts. The subsistence  hunt was largely criminalized as “game poaching” after Jack Taylor enclosed the commons in 1960 and the State of Colorado suddenly started to see dollars in sponsoring and regulating the business of trophy elk hunts and promotion of wildlife ranching.

hunt was largely criminalized as “game poaching” after Jack Taylor enclosed the commons in 1960 and the State of Colorado suddenly started to see dollars in sponsoring and regulating the business of trophy elk hunts and promotion of wildlife ranching.

The latest battle involves the principal historic and southernmost route for access to La Sierra through the myriad Torcido Creek trails. The main Torcido access road is visible in historical photographs as a county road dating back to before the 1960s and indications from those photos suggests the road and trails were by then many decades in use. Old-timers I have spoken with recount that the Torcido Creek drainage provided access to several important grazing and hunting grounds including, to the south and over the range crest, the upper reaches of the Valle Vidal in what is now public land in New Mexico. The Torcido was also a conventional route linking to the Cuates Creek drainage and its meadows and outstanding (now logged-out) subalpine spruce-fir forests. The Torcido also provided access to trails leading up and over into the Alamosito Creek meadows due north-northeast across La Sierra itself.

What the plaintiffs in this new case are alleging is that the subdivision owners and managers are interfering with the use rights of the heirs and successors since the road that has been blocked is a major historic point of access to critical use areas across the common lands.

The plaintiffs list, seeking class certification inclusive of all heirs and successors in the Lobato v. Taylor case, is led by Pete E. Espinoza, Jr., a rancher and former County Sheriff; Joe Gallegos, a former County Commissioner, San Luis Peoples Ditch Mayordomo, and Colorado Centennial Farmer; Juanita Martinez, a farmer and land rights activist; Shirley R. Otero, a farmer and former President of the Land Rights Council; and Delmer Vialpando, a rancher and current President of the Sangre de Cristo Acequia Association.

One key legal point in the initial pleadings will be the determination that the Torcido Creek Road has been, and should continue to be, considered as a county road under C.R.S. § 43-2-201(1)(c). This would help establish a bona fide basis for a claim of prescriptive easement by the beneficiaries of the Lobato v. Taylor certified class with access rights to La Sierra.

We will report on this lawsuit as it progresses through the Colorado district and presumably appeals courts. The principal aim of the plaintiffs, as recently related to me by three of the participants, is the need for the community to assert and defend clear access points and routes for access to La Sierra based on historic patterns of use in place since the 1840s.

My own interpretation of the significance of this claim is that it could have some unintentional effects that go well beyond the justly articulated issue of access rights to the commons. The presence and assertion of the “commoners” — engaging in their constitutionally-protected rights of access — may discourage the subdivision developers and investors from actually developing the various subdivision units affected by this case. Earlier efforts to resist the approval of these subdivisions as a threat to the integrity of the watershed of the acequias may also come to play an important corollary role shaping and informing this struggle as it continues to unfold.

Devon G. Peña, Ph.D., is a lifelong activist in the environmental justice and resilient agriculture movements, and is Professor of American Ethnic Studies, Anthropology, and Environmental Studies at the University of Washington in Seattle. His influential books include Mexican Americans and the Environment: Tierra y Vida (University of Arizona Press, 2005) and the edited volume Chicano Culture, Ecology, Politics: Subversive Kin (University of Arizona Press, 1998). Dr. Peña is the founding editor of the Environmental & Food Justice blog (where this article originally appeared), and is a Contributing Author for New Clear Vision.

As a new owner of a lot along the Torcido creek road, I am being sued for access rights to the road. I have no problem giving access to locals for legitimate purpose, but i fear excessive development and trespass issues if i cave in and let the plaintiffs have their way. Any suggestions on what I should do to protect my rights? I only want ownership/use of a beautiful part of Colorado. Not a lawsuit.

1Dear land owner:

Because this case in just ow entering the litigation phase, and plaintiffs are entitled to their due process and equal protection rights, I will keep my comments brief.

First, of course you do! Many people want to live here because it is such a beautiful part of Colorado. That is why the multi-generational farmers that sued you and other land owners are fighting so hard to protect the mountain and watershed from over-development.

Second, that is not really the rationale underlying this lawsuit. Instead, it has to do with something the company that sold you this subdivision-lot probably failed to inform you about: The 2002-03 Colorado Supreme Court decisions in Lobato v. Taylor that restored the historic use rights mentioned in the blog post above. The heirs and successors of the Sangre de Cristo Land Grant have access and use rights to La Sierra Common and the Torcido gate is one of the traditional access points to the exercise of those rights.

Third, to keep this part of Colorado beautiful, would it not be reasonable to avoid the type subdivision developments that are occurring in our foothills and sensitive watershed zones like the one you purchased? We, the local farmers, do not object to people “owning” a beautiful patch of Colorado but when this threatens our existence as farmers, then we have no choice but to defend our own much older and established property rights.

It is funny how newcomers to our area think they are the only people with vested interests in property rights. What you are belatedly learning is that the original inhabitants also have property rights. The lawsuit could be settled in a very simple manner: Remove the barricades on the Torcido Gate and it’ll likely all go away. Encourage the other defendants to follow this course. Then, we can start the more difficult work of becoming good neighbors, but this will remain a challenge since it is hard to be kind and generous with neighbors that take what they want without asking what is really at stake or who will be harmed and do so without substantive regard or respect for the people that have been here for 150+ years.

Join us in protecting our Constitutionally guaranteed rights to our common and we will be happy to let you enjoy your beautiful part of Colorado. It would of course be better if we kept it beautiful by not in the first place building McMansions in a sensitive and historic zone of the Sangre de Cristo Land Grant.

2” It would of course be better if we kept it beautiful by not in the first place building McMansions in a sensitive and historic zone of the Sangre de Cristo Land Grant.”

My greatgrandparents taught me to honor the land. As a young girl we would journey to the San Luis Valley from our homestead near Westcliff and Canon City to visit the “beautiful place” with “good air”. They taught me to live simply, to harvest enough for the family, for the community and leave a bit for the thief in the night “for he shall surely come”. They did not need mansions or fences for they knew how to respect the culture that provided for the people, they knew humility and grace. They practiced the moral value of looking after the community, being stewards to the land by listening to it, observing it and engaging with it from the heart and with informed awareness as to its importance to our existence. They taught respect for the people who farm it, who cut its wood and channel its water, people who live simply and work hard yet with joy. The very thing you who build the big sub divisions and trophey homes proclaim you want, ” I only want ownership/use of a beautiful part of Colorado. Not a lawsuit.” is the very thing you threaten…you want to OWN not use. When you buy into a system that does not honor the past, does not engage healthfully the present and certainly does not protect the future you have broken a sacred trust and that is a moral crime. Just because something is available does not mean it is right to impose inappropriate methods for using it. In this fragile landscape it is vital to act with great caution, not to impose upon it or the culture that was born from it but rather to learn from it, to participate with and in it and to do so with gratitude, honor and a humble spirit.

3It would be a grand day to see the McMansions torn down and the fences pulled up!

Donna D’Orio